The Band – Music From Big Pink

Music From Big Pink (1968)

B

1. Tears Of Rage 2. To Kingdom Come 3. In A Station 4. Caledonia Mission 5. The Weight 6. We Can Talk 7. Long Black Veil 8. Chest Fever 9. Lonesome Suzie 10. This Wheel’s On Fire 11. I Shall Be Released

In 1984, Bob Geldof got on the phone with all the most self-righteous pricks in the music business and was like, “Hey, I’ve got this song about starving African children, wanna help me sing it?” And Band Aid was b

Oh, wait a minute. Can you blame me for being confused, though? The Band could potentially be any band with the word “Band” in its name. Way to not foresee the concept of being Googleable in 1968, assholes!

Fortunately, the Band did seem to have the foresight to realize that the future of rock ‘n roll wasn’t going to be based on trying to outdo Sgt. Pepper, which seemed like it might end up being the case during the exactly thirteen months that separated Pepper and Music From Big Pink. It would forever proceed in cycles from 1968 on, from excess to bare bones, from psychedelia to roots rock, from prog to punk, from 80s synth schlock to grunge and alt-rock, from dubstep to whatever the fuck is coming next. John Wesley Harding was first, but then came Sweetheart Of The Rodeo and Big Pink. And by the time Beggars Banquet and The White Album came out a few months later, the dance hall fruitiness and acid trip jamming that dominated 1967 seemed but a distant memory. Suddenly everyone wanted to hear their favorite longhaired rock stars play acoustic guitars and sing country songs! Thank god. Rock ‘n roll needs a good stripping down every few years, and the Band and their influence was played pretty significant part in making that happen the first time and turning 1968-1972 among the best and most productive (and easily the most celebrated) periods in rock history.

With that, and forty five years of hindsight, in mind, Big Pink is a perplexing mix of the ramshackle and the overcooked, with only about a third of the record finding the sweet spot betwixt and between the two. Not being an old person, I honestly don’t know what was more mind blowing to listeners and fellow musicians in 1968: the simplicity and unvarnished arrangements of songs like “The Weight,” or Garth Hudson’s synths on “In A Station” and “This Wheel’s On Fire,” which may have seemed new and exciting back then, but now just sound like noises that might have come out of my old Game Boy. I guess the former is what defines the Band for most listeners, and their down home sloppiness is what appeals to me about their best work, at least. But my tolerance for the particular ways in which they lack polish on Big Pink only goes so far – that being, not much farther than it does for overweening ballads and arrangement decisions of questionable taste.

As a result, it’s taken quite a while for Big Pink to reveal its considerable merits and mostly strong songwriting to me. But I’m still not able to overlook some pretty glaring flaws, unlike seemingly everyone else in the world, who awards it five stars and loud, sloppy critical blowjobs. Even the good songs feature unfortunate traits, which range from momentarily distracting (the deflating, out of place funeral march-style bridge in “Chest Fever”) to nearly enough to ruin the experience outright (the orgy of violently botched vocals that occurs atop the otherwise nice and punchy piano rocker “To Kingdom Come.” If that is indeed Robbie Robertson singing lead vocals for allegedly the only time on a Band record, then it’s no wonder they used to turn off his mic during concerts, as Levon has claimed they did). Plus there’s not nearly enough Levon – he only gets one and a half lead vocal showcases, the one being “The Weight” and the half being parts of “We Can Talk,” even though his vocals are the only ones that sound practiced and consistently in tune. Fortunately, Robbie would immediately realize the error of his ways and give Levon a lot more to sing on all subsequent Band albums. But Big Pink suffers from him not having realized sooner. I mean, seriously, is that the best take they could get out of Rick Danko for his verse of “The Weight”? From the first time I heard that song on the radio, I always thought he sung that part like shit.

I think Big Pink, quality-wise, can be divided into separate thirds that conveniently follow one another in the track order. The first third starts the album off on inoffensive and mostly solid but hardly thrilling ground. The first track is the popular Bob Dylan/Richard Manuel-penned “Tears Of Rage,” which originated from The Basement Tapes session. I never even particularly cared for the stripped down Basement Tapes version of this song. Lucky me – this version includes a slow-as-molasses, almost melodramatic tempo and Robbie Robertson, his guitar filtered through a Leslie cabinet, noodling incessantly in my right ear for five and a half minutes, I’m bound to get bored sooner rather than later. Manuel provides a truly breathtaking vocal performance that threatens to turn the song into something memorable, and the New Orleans-y trombones are a nice touch. But ultimately it feels like they’re trying to do too much with a song that there was never much to in the first place. Manuel’s “In A Station” sounds like the template for every indie rock band that has attempted to write a “dreamy” 60s-style pop song. Same kind of fruity synth line and everything. Robertson’s “Caledonia Mission” alternates folksy strumming with 50s boogie rock choruses while stringing together distractingly meaningless rhymes like “I do believe in your hexagram/But can you tell me how they all knew the plan.”

The record really starts picking up steam from there, starting with “The Weight,” which, sadly, will soon, if it hasn’t already, be surpassed by Old Crow Medicine Show’s “Wagon Wheel” as the song sung most times, all time, by drunken groups of white guys with acoustic guitars. “We Can Talk” is pretty standard meat and potatoes country rock, but it’s strong, as is the version of the haunting 1959 country song “Long Black Veil.” This isn’t my favorite version of the oft-covered tune—the groove is oddly stiff for the usually loosey goosey Band—but it’s one of my favorite songs of all time and pretty hard to fuck up. The record then hits its peak with the massive arena-rock-before-there-was-arena-rock of “Chest Fever.” Hudson’ towering organ, complete with a solo intro that sounds derived from a Bach chorale prelude, is one contribution of his that I will never ever complain about – it’s pretty powerful stuff. The song just kind of lumbers along with its three-note riff at a grinding tempo, but aside from the aforementioned bridge that pretty much derails the whole thing for about twenty seconds, it damn sure rocks in its way.

After that, the album peters out pretty darn weakly with Manuel’s turgid ballad “Lonesome Suzie” and two more squandered Dylan songs from The Basement Tapes. They blow through “This Wheel’s On Fire” (co-written with Danko) at a flippant tempo that completely negates the song’s inherent creepiness, and that revolting synth tone certainly doesn’t help. And finally, everyone always gushes about this version of “I Shall Be Released” and Manuel’s falsetto vocal in particular, but I can’t stand either. It’s one of Dylan’s greatest songs, but here sounds like something meant to be played over the closing credits of The Bold And The Beautiful and sung by a pubescent teenager whose voice is right in the middle of changing. I don’t care what everyone else thinks. It sucks.

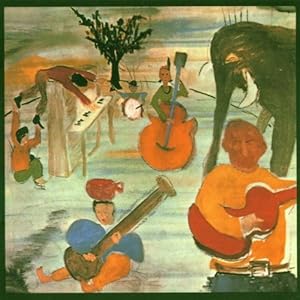

This is the longest review ever, so let me quickly close by saying that Bob Dylan painted the cover art, which has an elephant on it. Elephants are cool.

I hardly know where to begin to respond to this abomination masquerading as analysis. Perhaps Ian Cohen has abducted the great Mr Etc and is posting here as a doppelganger to destroy the well-earned reputation of our noble blogger. Hopefully he will escape before being turned into a decrepit zombie critic like evvabuddy else in the dead zone of music criticism. Afew meager points as illustration:

“…the dance hall fruitiness and acid trip jamming that dominated 1967…”. HooBoy does that have the odor of decay!

I would give you these transcendent artists as refutation(only a smattering, respecting the limits of space and the debilitating effect of confused anger): The Stones, Doors, Byrds, Pink Floyd, Moby Grape,

Big Brother, Jimi Hendrix, Tim Buckley, Buffalo Springfield, and the very apex of the Motown/Stax soul scene; James Brown, Otis Redding, Aretha, Smokey Robinson, Sam and Dave, Wilson Pickett,

Marvin Gaye and etc & etc & etc. Acid trip jamming?? I think not.

Next up is a two option question. Option #1 “Rock ‘n roll needs a good stripping down every few years, and the Band and their influence was played pretty significant part in making that happen…their down home sloppiness is what appeals to me about their best work” or option #2 ” my tolerance for the particular ways in which they lack polish on Big Pink only goes so far Pick one. You can’t have both.

And also this: “even though (Levon”s) vocals are the only ones that sound practiced and consistently in tune.”</I. Unlike Mick Jagger, Neil Young, Roger Daltry, Jack White, Hendrix, Jim Morrison and ad infinitum.

You speak as an opera critic here. They pilloried Pavarotti with similar slights.

Your literary esteem for "Chest Fever " is well done, but your disdain for the bridge is a bridge too far.

Lastly for now, turgid and "overweening" ballads and slooww tempos are not a weakness here; they expand the dynamic range of this collection which leads the listener on a sonic and lyrical journey through a new world (at least it was new in '68) of commercial rock. Thanks to Bobby Z. for bringing this to fruition.

Oh, and "I shall be Released" was an epic and very personal experience for many of us at the time. If your objections to it are rooted in the context of present day standards, then you are missing a huge part of what this music meant, not only for the listening devotees, but, as you say: the Band and their influence …played pretty significant part in …turning 1968-1972 among the best and most productive (and easily the most celebrated) periods in rock history”. Sorry Mr Etc, but “Released” contributed a major transformative legacy to the evolution of subsequent bands. Other than these quibbling, minor objections, the post has merit. Just please don’t go to the dark side.

Begone Ian Cohen, the exorcist is nigh.

I think Victoid needs his own blog!!