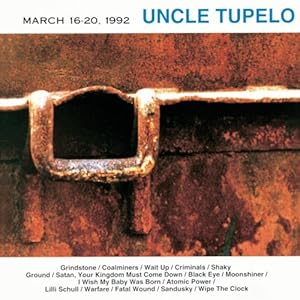

Uncle Tupelo – March 16-20, 1992

March 16-20, 1992 (1992)

A+

1. Grindstone 2. Coalminers 3. Wait Up 4. Criminals 5. Shaky Ground 6. Satan, Your Kingdom Must Come Down 7. Black Eye 8. Moonshiner 9. I Wish My Baby Was Born 10. Atomic Power 11. Lilli Shull 12. Warfare 13. Fatal Wound 14. Sandusky 15. Wipe The Clock

Do you know what Osama bin Laden’s professed goals were for carrying out the 9/11 attacks? To goad the US military into endless quagmires in the Middle East, in the process wreaking havoc on our financial system. Well, thanks to the extreme stupidity and rash incompetence of the Bush administration, it sorta looks like Osama’s vision came true, doesn’t it? Of course, I must admit that in his vision, he probably wasn’t planning on being shot in the face by Navy SEALs, but other than that, his whole strategy has pretty much worked to a tee. I’m sorry, it’s just that today is the 10th anniversary of 9/11 and everyone in the media is bashing us over the head with “remembrance.” I mean, I was only 10 at the time, but I certainly remember where I was and what I was doing that day. I remember that I happened to be on a trip at my school’s farm in upstate New York that week, and when one of our teachers at the farm, John, gathered us for a meeting late on Tuesday morning and told us what had happened, I was pretty scared because I knew my dad was scheduled to work down at the World Trade Center for that whole week. I had even been down there with him no more than a week before and saw the stage he was building (fortunately he was off that day, and his buddies that were working managed to get away safely. There’s tons of stories like that, about people showing up late or not going to work that day. It’s amazing). I remember that after I found out he was safe, I didn’t, as a kid, even come close to understanding the magnitude of the damage, whether physical or symbolic. I remember that when I got back to the city on Friday, the first thing I did was ask my dad if we could go downtown and see it, because my mental image was of the towers lying on their side rather than the mass of twisted metal and smoke that it turned out to be, and I thought that would be cool to look at. I remember how when we got home, I wanted to watch Digimon but the news was on every channel and my dad made me turn off the TV because he didn’t want me to see the stuff they might be showing. I remember the grief we all felt, and still feel, at the horrific and senseless deaths of 3,000 innocent people – not to mention for the families they left behind and, eventually, the first responders who Republicans tried their darndest to deny the health care that might help them stave off their premature deaths from various types of cancers and other horrible ailments. I remember the great sense of community we felt, in NYC at least, in the aftermath of the attacks. But when I think about 9/11, all that is not what I remember. I remember “Go shopping,” the senseless macho talk, the fear stoking, the despicable patriotism-questioning of “you’re anti-American if you don’t love George W. Bush and whatever he decides to do with our troops,” “My Pet Goat,” the Patriot Act, the color-coded “Terror Watch” chart, the shameless exploitation of the tragedy for political gain that continues to go on today, the wars and the rampant constitutional and human rights violations that have gone with them, and the mess that the horrible mismanagement of the aftermath has landed us in. I simply cannot disassociate that day from the sickening shit that came after, so forgive me, but I’d rather forget.

March 16-20, 1992 is about the pain and suffering of America’s dark underbelly, both past and present. The kind of suffering that’s caused by the same people that fucked up our country post-9/11. “There’s no justice in the hall/We’re all criminals waiting to be called.” True dat, Jay. He had George Bush, Sr. in mind, but he might as well have been singing about his son, or his Nazi-supporting father, or hell, King George. The rich and powerful fuck the poor in the ass; it was happening in America in the 1920’s and Gob know how much older than that some of these songs are, and it’s only getting worse today. And there’s no better chronicle of that struggle than the American folk tradition.

Some background: Jay, Jeff and Mike met Peter Buck while on tour in Athens, Georgia and they agreed to team up for an album of acoustic folk music. Now, this was at the height of Nirvana-mania, when all you had to do to grow your fan base was wear plaid, avoid showering, and play guitar with the ugliest distortion you could muster. So few bands would have the balls, much less the desire, to put out a record with no electric guitars on it and where half the songs were antiquated folk covers. But with the help of Buck, after spending five days in March ‘92 (guess which ones!) in his Athens studio (with assistance from David Barbe, the future Drive-By Truckers producer who served as an engineer on this album), they turned in this pristine collection of haunting American folk music, and the best record of the band’s preciously short career. They explore the dark side of the world we see through the prism of Alan Lomax’s Anthology of American Folk Music, as they tackle the old standby topics like murder (“Lilli Shull”), vices (“Moonshiner”), economic woe (“Coalminers”) and religion (“Satan, Your Kingdom Must Come Down”). You’ve probably heard a lot of these songs before from other versions, especially “Moonshiner,” since Dylan did it. But—and I don’t say this lightly—of the countless versions of that song, Farrar’s mournful take might be the definitive one, and it’s certainly one of Uncle Tupelo’s signature moments. So is “Sandusky” – lemme tell ya, instrumentals almost always bore me, but this one is just ridiculously beautiful.

Every cover here is extremely well-chosen and impeccably rendered, and the originals sit beautifully beside them; Farrar, like always, seems to be trying to emulate the expression of socio-political strife found in the cover tunes he selects (one of which is “Coalminers,” where he sings, “Let’s sink this capitalist system to the darkest pits of hell.” Yeah, sure, we all believe you were a Depression-era radical socialist, Jay. But really, he does sound passionate and convincing). But he succeeds to far a greater degree than he had in the past: “Grindstone,” half country barnburner, half waltzing weeper, is his best, while “Shaky Ground” and “Criminals” sound like the dying echoes of class-oppressed lives. And his solo turn on “Wipe The Clock” approaches “Still Be Around”-level beauty. Tweedy’s originals are once again more inward-focused, and they’re just stunning little oddities with bubbling guitar lines – “Wait Up” and “Black Eye” are still two of the strangest and most emotional creations of his career. And that instrument you hear when they switch to the D chord is not a pedal steel, but rather Peter Buck “playing” feedback with his Rickenbacker. How cool is that? It doesn’t make up for Around The Sun or anything, but it’s neat.

But hey, don’t be so quick to give all the credit to Jay, Jeff and Peter. The real MVP of this album is Tupelo compadre Brian Henneman, who would soon go on to be the frontman for the Bottle Rockets, a band that has now lasted about three times as long as Uncle Tupelo. He’s one of the best guitarists you’re ever going to hear, and he’s all over this thing. Not just playing guitar, either, but also mandolin (and not just any mandolin, but rather Buck’s “Losing My Religion” mandolin! Man, do these guys get hooked up with gear or what?), banjo, slide, and an unsung but cool-sounding mandolin-like contraption called a bouzouki (he uses it most prominently to play the melody line of “Satan, Your Kingdom Must Come Down”). He’s just a ridiculously gifted lead player, and his contributions are vital to making the album as good as it is.

March is a borderline A+ for sure, for two reasons: first, Tweedy’s utterly drab “Fatal Wound,” a song that does not interest me at all. Second, and more importantly, there’s no humor. Humor and entendre is a crucial ingredient in just about all folk music traditions, and though the album touches on and excels at just about every other aspect of American folk music except this one, Farrar’s unrelenting solemnity doesn’t allow much room for laughs (which isn’t an aspect of his persona that has, or probably ever will go away). It’s why March can’t properly be termed a definitive reimagining of American folk. Even the few moments that are musically, by comparison, light and buoyant (the Louvin Brothers classic “Atomic Power,” the Jeff-sung “Warfare”) are about, you know, dying and stuff. If I had a reason to drop this record down to an A, it would be that. And maybe tomorrow, I’ll change my mind, but today, September 11, an A+ it is.

This certainly deserves the A+ grading, in my opinion. Great record.